A Document on Human Fraternity:

An Islamic Perspective

Introduction

The “Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together,” signed by Pope Francis and Sheikh al-Azhar Ahmad al-Tayyeb, on February 4, 2019, in Abu Dhabi, marks a historic milestone in Pope Francis’ relationship with the Muslim world. It is, in fact, the first document jointly signed by the head of the Catholic Church and a Muslim leader, the Grand Imam of al-Azhar, one of the most globally recognized Islamic religious institutions. Notably, it was unveiled and signed during the first visit of a pontiff to the Arabian Peninsula, the cradle of Islam. Significantly, the Document commemorates the 800th anniversary of the encounter between St. Francis and Sultan al-Kamil in Damietta, Egypt. In honor of this event, the Pope chose to visit two Arab nations with Muslim majorities: the United Arab Emirates, in the far east of the Arab world, and the Kingdom of Morocco, in the far west. Symbolically, the Pope, who bears the name of the Saint, wanted to meet two “sultans,” and to sign a Document with a prominent religious authority based in Cairo, the heart of the Arab world. This gesture represented an embrace of the Arab world from both ends during a challenging historical period for the entire region. The first meeting between Francis and the Sultan was at the time of the Crusades, and the recent meeting coincided with a period marked by wars and conflicts, including those in Syria and Yemen, as well as the heightened tensions with Iran. Despite these challenges, the message persisted: to advocate for peace and rights in defiance of prevailing discord.

The Theological Framework

The Document provides an ethical roadmap or common ground of values, serving as a foundation for a shared global ethic. However, it extends beyond ethical discourse and common values to encompass a general theological framework that underpins values. It encompasses not only ethics but also faith and doctrine:

We, who believe in God and in the final meeting with Him and His judgment, on the basis of our religious and moral responsibility, and through this Document, call upon ourselves, upon the leaders of the world […]

From this perspective, Christianity and Islam not only share values but also faith in God and human dignity, they share the same responsibility before God and humanity. Islam and Christianity are not two opposing or warring religions, but have a solid theological and ethical basis, which allows for dialogue, solidarity, and a common mission in the service of humanity.

From the preface, we read in the first sentence:

Faith leads a believer to see in the other a brother or sister to be supported and loved. Through faith in God, who has created the universe, creatures, and all human beings (equal on account of his mercy), believers are called to express this human fraternity by safeguarding creation and the entire universe and supporting all persons, especially the poorest and those most in need.

This implies that the absence of love and solidarity wounds one’s faith. A Muslim who harbors hatred towards a Christian is less Muslim, just as a Christian who harbors hate against a Muslim is less Christian. Conversely, the principle is broader because it speaks of believers in general. Faith is a love expressed in life through solidarity. A second important point in the preface is what might be called cosmic solidarity and integral ecology. There is a relationship of complementarity between “human fraternity” and “safeguarding creation,” as “cosmic fraternity” among all creatures. The link between theology and ethics appears clearly through a series of “in the name of…,” reminiscent of the Islamic basmala: [1]

In the name of God […]

In the name of innocent human life that God has forbidden to kill […]

In the name of the poor, the destitute, the marginalized, and those most in need whom God has commanded us to help […]

In the name of orphans, widows, refugees, and those exiled from their homes and their countries.

In the name of all victims of wars, persecution, and injustice; in the name of the weak, those who live in fear, prisoners of war, and those tortured in any part of the world, without distinction.

In the name of peoples who have lost their security, peace, and the possibility of living together, becoming victims of destruction, calamity, and war.

In the name of human fraternity that embraces all human beings, unites them, and renders them equal.

In the name of this fraternity torn apart by policies of extremism and division, by systems of unrestrained profit or by hateful ideological tendencies that manipulate the actions and the future of men and women.

In the name of freedom, that God has given to all human beings creating them free and distinguishing them by this gift.

In the name of justice and mercy, the foundations of prosperity and the cornerstone of faith.

[…]

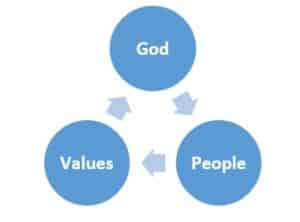

This long basmala can be condensed into three points: in the name of God, in the name of the people, especially the oppressed and the weak, and in the name of common values. Those who believe in God must believe in the human being and in the fundamental values of life and fraternity. It forms a cycle of values, which can be represented in the following diagram:

This recalls the Qur’anic phrase, fi sabil Allah, meaning “in the way of God”, which is reiterated 44 times, emphasizing the path of humanity and the pursuit of the common good. In the oath of Khoda-i Khidmatgar, “the servants of God,” the unarmed army founded by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in 1929, the profound meaning of worship and service (‘ibada) is well explained: “I am a servant of God: since God has no need of any service, to serve His creation is to serve Him. I promise to serve mankind in the name of God.” [2]

Full and Inclusive Citizenship

The Document is addressed to women and men in various fields such as politics, economics, culture, religion, art, mass media; in short, everyone. From the list of people and groups to whom the Document is addressed, it can be understood that religious leadership is only one component of the desired change, which needs the collaboration of all social and intellectual workers. This hints at a particular vision of the relationship between religion and the public space. Religion is seen as critical consciousness at the national and international levels. To achieve a broad impact locally and globally, we need to be credible and consistent, so religious individuals are called to take a leading role: “We ask ourselves” first.

Moreover, the Document is directed towards both the West and the East, addressing issues pertinent to the South as well as the North, without asserting religious or cultural superiority or privileges. This raises the question of representativeness, especially for al-Azhar. It is fair to ask: to what extent is this Sunni Muslim institution, despite its millennia-old history, representative of the Muslims of East and West today? The mode of representation is not the same between the Catholic Church and al-Azhar. The Church has its typical hierarchical structure and organizational system, which is the exception and not the rule at the global level; no other religion has such a complex and extensive structure as Catholicism. Al-Azhar, on the other hand, remains a Sunni institution, inherently limiting its inclusivity to non-Sunnis. Moreover, it is an Egyptian institution, which has no real power outside Egypt. Even inside Egypt, the religious power of al-Azhar is totally under state control, being part of the Egyptian state. Despite these limitations, al-Azhar’s representativeness lies precisely in its traditional academic reputation, as a university that has welcomed students from all over the world, from North Africa to Indonesia, for centuries. Furthermore, it serves as a point of reference for many Muslims on the five continents, without claiming a monopoly or exclusivity.

The question of representativeness is intrinsically linked to the question of credibility, as without it, there’s a risk of formalism. Consequently, the Document’s credibility stems not only from the representativeness of its signatories and institutions, but also from its content, which responds to the real expectations and needs of a wide audience that goes beyond institutional boundaries. In this way, representativeness not only precedes and supports the Document, but is nourished by its contents, and above all by their implementation. It is an ethical and dynamic representativeness. A complex and canonical structure, such as the Catholic one, is representative at the official and formal level, but its representativeness is concretized when it truly represents the spirit and the Gospel and human values. From this point of view, the Document cannot be disconnected from Pope Francis’ reform project, nor from the reform of religious thought in the Islamic sphere. Al-Azhar itself has regained at least some of its credibility, embracing the popular desire for change after the 2011 revolution, a desire that is reflected in the Azharian documents as:

– “Al-Azhar Document on the Future of Egypt” (2011), which is the synthesis of Egypt’s national dialogue. The fruit of the works of the Egyptian House, al-bayt al-misri. The role of Mahmoud Azab (d. 2014), the advisor to Sheikh al-Azhar, was a leading role in coordinating the work.

– “Declaration of al-Azhar and Intellectuals in Support of the Will of the Arab Peoples” (2011), also called “Document of the Arab Spring and Support for Arab Liberation Movements.”

– “Al-Azhar Document on the System of Fundamental Freedoms” (2012), which deals with four types of freedoms: freedom of belief, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of scientific research, and freedom of literary and artistic creativity.

– “Al-Azhar Document for the Rejection of Violence in Egypt” (2013).

– “Al-Azhar Document for Women’s Rights” (2013).

– “Al-Azhar Declaration for Citizenship and Coexistence” (2017), which was released at the end of a conference organized in Cairo. Delegates from more than fifty countries attended the conference, including leaders of Eastern churches, clergy, thinkers and politicians, Muslims, and Christians, from different schools and denominations.[3]

The “Human Fraternity” Document is notably influenced by two other documents: “the Document on the Future of Egypt” and “the Declaration on Citizenship and Coexistence,” because of their focus on the concept of full citizenship.

Another aspect to highlight is that representativeness and credibility do not depend only on the signatories, but also on the recipients, on us: what do we intend to do with the Document? The value of any document depends not only on the content, but also on the reception and application. A perfect document, no matter how well crafted, holds little value if it mere sits on the shelves of a library. The positive response of civil societies and all social factors is decisive.

In addition to the question of “who represents whom,” many of the issues, and a large part of the values and solutions mentioned in the Document are truly “of the East and of the West.” This is evident throughout the text, when it addresses the impact of extremism and intolerance, stating: “History states that religious and national extremism and intolerance have produced in the world, both in the West and in the East, what might be called the signs of a piecemeal third world war.” These are global problems and challenges that require a global response.

The Document occupies the shared space where religious values intersect with secular values and where politics converges with religion, in the noblest sense of words. In other words, it is about believers who are both citizens and leaders in the public space, which is open to all, including non-believers. The Document clearly emphasizes the fundamental values of equality and full citizenship:

The concept of citizenship is based on the equality of rights and duties, under which all enjoy justice. It is therefore crucial to establish in our societies the concept of full citizenship and reject the discriminatory use of the term minorities which engenders feelings of isolation and inferiority.

These statements are important in the Islamic context, particularly as certain minorities, such as Christians, suffer from various forms of discrimination, sometimes considered second-class citizens albeit not openly. In other countries, Muslim minorities face persecution, like in Myanmar, China, and India. Even in regions like Europe and North America, where democracy is more firmly established, concerns arise over the surge of Islamophobia and anti-Semitism, especially with the emergence of far-right movements and parties.

The Document advocates for transcending the derogatory notion of “minority” to achieve full citizenship, guaranteeing equality in rights and duties. This principle of legal equality finds its expression in the secular state, where all citizens are treated equally. While the Document does not use the terms laicity and secularism, the underlying concept can be discerned. What truly matters is the idea, not the terminology. For this reason, we find traces of political theory in the Document, elucidating the relationship between religion and the public space: Religion represents an ethical and moral conscience in society and in the world, without asserting privilege or claiming a monopoly.

Freedom and pluralism

Among the many topics that the Document deals with the link between freedom, diversity, and divine Wisdom. Religious pluralism is seen as a positive thing that is part of the Divine Wisdom:

Freedom is a right of every person: each individual enjoys freedom of belief, thought, expression and action. The pluralism and the diversity of religions, color, sex, race, and language are willed by God in His wisdom, through which He created human beings. This divine wisdom is the source from which the right to freedom of belief and the freedom to be different derives. Therefore, the fact that people are forced to adhere to a certain religion or culture must be rejected, as too the imposition of a cultural way of life that others do not accept.

The Catholic Church has gradually freed itself from the theological exclusivism represented by the formula Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus, adopting an inclusivist stance. This approach underscores the centrality of Jesus Christ in salvation, which is possible outside the Church but always through Him. It is not a question of pluralism in the absolute sense, but rather of a relative pluralism, salvation is possible without belonging to the Church, but through Christ, even if in hidden ways and without the awareness of those saved. Concurrently, the Magisterium of the Church remains attentive to the question of theological and ethical relativism, seen as a danger to the Christian faith.[4] This explains the debate, if not the criticism, that the above-mentioned paragraph has aroused, especially in Catholic circles, because it touched on a sensitive issue, which prompted Pope Francis to respond during his speech at the general audience on April 3, 2019, in St. Peter’s Square:

But some might ask themselves: but why is the Pope going to the Muslims and not just to Catholics? Because there are many religions, and why are there many religions? Along with the Muslims, we are the descendants of the same Father, Abraham: why does God allow many religions? God wanted to allow this: Scolastica theologians used to refer to God’s voluntas permissiva. He wanted to allow this reality: there are many religions. Some are born from culture, but they always look to heaven; they look to God. But what God wants is fraternity among us and in a special way, this was the reason for the trip, with our brothers, Abraham’s children like us, the Muslims. We must not fear differences. God allowed this. We should be afraid were we to fail to work fraternally to walk together in life.

In the Islamic circle, we do not have explicit statements from al-Azhar, which in any case remains a conservative circle, not very open to the new themes of the theology of religions.[5] However, this does not negate the presence of many Qur’anic verses indicating that diversity and plurality are part of God’s cosmic plan; it is willed by the Lord, indeed it is His general creative way; the world was created colorful:

Have you not considered how God sends water down from the sky and that We produce with it fruits of varied colors; that there are in the mountains layers of white and red of various hues, and jet black; 28 that there are various colors among human beings, wild animals, and livestock too? It is those of His servants who have knowledge who stand in true awe of God. God is almighty, most forgiving (Q 35, 27-28)[6]

The same rule applies to religions, their diversity is willed by God for a supreme Wisdom, to push mankind to compete in good; transforming negative jealousy into a fair competition in the service of humanity:

Each community has its own direction to which it turns: race to do good deeds and wherever you are, God will bring you together. God has power to do everything (Q 2, 148).

We have assigned a law and a path to each of you. If God had so willed, He would have made you one community, but He wanted to test you through that which He has given you, so race to do good: you will all return to God and He will make clear to you the matters you differed about (Q 5, 48).

If God had so pleased, He could have made them a single community, but He admits to His mercy whoever He will; the evildoers will have no one to protect or help them (Q 42, 8).

This path that is different for everyone, is bestowed by God Himself. Therefore, it is a question of a legitimate diversity and plurality since they are willed by God. The Qur’an states here that if God had willed, He would have made one community; but he did not. Instead, it was His own will that established this plurality of ways, which, however, have God Himself as the final goal. The new theologians of Islam seek to develop this pluralistic Qur’anic line, in dialogue with the Christian theology of religions and with new hermeneutical methodologies, to overcome the still dominant traditionalist exclusivism.[7]

Despite this reference to the theology of religions, the Document appears primarily concerned not with elucidating the phenomenon of religious plurality, which in any case remains an inscrutable aspect of Divine Wisdom, but rather attempts to manage this plurality in a positive way, seen as a good and as an opportunity. It is the ethics of pluralism that prevails over theology. The Document seems apparently wary of theological dialogue:

Dialogue among believers means coming together in the vast space of spiritual, human, and shared social values and, from here, transmitting the highest moral virtues that religions aim for. It also means avoiding unproductive discussions.

One could understand “unproductive discussions” as a call to avoid theological dialogue, which seems to be a distraction in the face of real common challenges, or a cause of quarrel and discord. However, the sentence is quite short, and cannot support such a categorical statement.

Nonetheless, theological dialogue is inevitable, it is enough to read the Document carefully to see that ethical values are closely linked to their theological background. The Document mentions faith in God and human dignity, responsibility before God on the Day of Judgment, which are doctrines that can be shared. The Document contains ideas related to the theology of religions and liberation theology, although they are expressed in an allusive and concise way. Previously, the Declaration “Nostra Aetate” also acknowledged the doctrinal communalities between Muslims and Christians. The problem lies in the polemical and aggressive attitude that tries to prove a certain supremacy by diminishing the value of the other who is different.

Pope Francis’ address to the meeting organized by the Pontifical Faculty of Theology of Southern Italy in Naples on 21 June 2019, on the theme “Theology after Veritatis Gaudium in the context of the Mediterranean,” represents a decisive step in the recognition and legitimization of theological dialogue. The Pope speaks of an interdisciplinary theology of hospitality and dialogue, a theology of reception and listening.

Certainly, interreligious and comparative theology provides a platform for mutual growth in understanding the divine will that created the world in this plural and complex way. To find a common language that makes communication and sharing of ideas and methodologies easier and deeper. To think of theology in a universal way, so the claim to belong to universal religions is no longer an empty slogan but a concrete reality. While the Document offers some promising elements, much remains to be done to expand fraternity to include theological brotherhood and sisterhood.

References

Abdel Haleem, M. A. S., The Qur’an, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Abdelnour, Mohammed Gamal, A Comparative History of Catholic and Ašʿarī Theologies of Truth and Salvation: Inclusive Minorities, Exclusive Majorities, Leiden-Boston: Brill 2021.

Dupuis, Jacques, Toward a Christian Theology of Religious Pluralism, New York: Orbis Books, 1999.

Easwaran, Eknath, Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Badshah Khan, a Man to Match His Mountains, Tomales: Nilgiri Press,1999.

Khalil, Mohammad Hassan (ed.), Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Khalil, Mohammad Hassan, Islam and the Fate of Others: The Salvation Question, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Knitter, Paul F., Introducing Theologies of Religion, New York: Orbis Books, 2002.

Knitter, Paul F., Jesus and the Other Names: Christian Mission and Global Responsibility, London: Oneworld Publications, 1997.

Lamptey, Jerusha Tanner, Never Wholly Other: A Muslima Theology of Religious Pluralism, Oxford University Press, New York, 2014.

Mokrani, Adnane & Brunetto Salvarani, Dell’umana fratellanza e altri dubbi, Milano: Edizioni Terra Santa, 2021.

Shah-Kazemi, Reza, The Other in the Light of the One: The Universality of the Qur’ān and Interfaith Dialogue, Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 2006.

Soroush, Abdulkarim, Expansion of Prophetic Experience: Essays on Historicity, Contingency and Plurality in Religion, tr. N. Mobasser, Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2009.

Websites

A Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/travels/2019/outside/documents/papa-francesco_20190204_documento-fratellanza-umana.html

A.A., Al-Azhar Declaration on the Future of Egypt, Rajab 1432 A.H.-June 2011, Alexandria: al-Azhar and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina Coordinating Committee. https://www.bibalex.org/Attachments/english/elazhar.pdf

Al-Azhar official website: http://www.azhar.eg/AzharStatements

Pope Francis’ discourse to the meeting organized by the Pontifical Faculty of Theology of Southern Italy in Naples, on 21 June 2019, on the theme “Theology after Veritatis Gaudium in the context of the Mediterranean”: http://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2019/06/21/0532/01104.html?fbclid=IwAR0DH0kGZEOPdo-anGroEenZhTalxNXDZttDK3bIEn1YlTJV59gfEM8jUBI

Pope Francis’s speech during the general audience on April 3, 2019: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/audiences/2019/documents/papa-francesco_20190403_udienza-generale.html

[1] Basmala is the Islamic formula that is recited at the beginning of Qur’anic chapters or before any activity, often translated as “in the name of God the Clement the Merciful.”

[2] Eknath Easwaran, Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Badshah Khan, a Man to Match His Mountains, Tomales: Nilgiri Press,1999, p. 111.

[3] See al-Azhar’s documents on its official website: http://www.azhar.eg/AzharStatements. “Al-Azhar Document on the Future of Egypt” is translated into English, French and German. Translations are published with the Arabic text by the Library of Alexandria in collaboration with al-Azhar: Al-Azhar Declaration on the Future of Egypt, Rajab 1432 A.H.-June 2011, al-Azhar and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina Coordinating Committee. The booklet is available online: https://www.bibalex.org/Attachments/english/elazhar.pdf

[4] On the Christian debate on the theology of religions, see: Jacques Dupuis, Toward a Christian Theology of Religious Pluralism, New York: Orbis Books, 1999. Paul F. Knitter, Introducing Theologies of Religion, New York: Orbis Books, 2002. Jesus and the Other Names: Christian Mission and Global Responsibility, London: Oneworld Publications, 1997.

[5] The work of the young Azhari scholar, Mohammed Gamal Abdelnour, is a good sign of openness to theological dialogue: A Comparative History of Catholic and Ašʿarī Theologies of Truth and Salvation: Inclusive Minorities, Exclusive Majorities, Leiden-Boston: Brill 2021.

[6] The Qur’anic translation used in this article is: M. A. S. Abdel Haleem, The Qur’an, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

[7] See for instance: Reza Shah-Kazemi, The Other in the Light of the One: The Universality of the Qur’ān and Interfaith Dialogue, Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 2006. Abdulkarim Soroush, Expansion of Prophetic Experience: Essays on Historicity, Contingency and Plurality in Religion, tr. N. Mobasser, Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2009. Mohammad Hassan Khalil, Islam and the Fate of Others: The Salvation Question, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Mohammad Hassan Khalil (ed.), Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. Jerusha Tanner Lamptey, Never Wholly Other: A Muslima Theology of Religious Pluralism, New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

This article is a modified and summarized translation by the author of a part of his book (with Brunetto Salvarani), Dell’umana fratellanza e altri dubbi, Milano: Edizioni Terra Santa, 2021, pp. 21-61.

Cover photo: Pope Francis on the left and Egypt’s Azhar Grand Imam Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayeb on the right sign documents during the Human Fraternity Meeting at the Founders Memorial in Abu Dhabi on February 4, 2019. Photo by Vincenzo Pinto / AFP.